imported>Kultokrat No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

|image = Polish Irri.png | |image = Polish Irri.png | ||

|caption = I am Król of World | |caption = I am Król of World | ||

|aliases = | |aliases = Most normal Polish ideology | ||

|alignments = | |alignments = | ||

[[File:Nation.png]] [[:Category:Nationalists|Nationalists]]<br> | [[File:Nation.png]] [[:Category:Nationalists|Nationalists]]<br> | ||

| Line 14: | Line 14: | ||

|family = | |family = | ||

|influences = | |influences = | ||

[[File:Nation.png]] | [[File:Nation.png]] [[Nationalism]]<br> | ||

[[File:Irredentism.png]] [[ | [[File:Irredentism.png]] [[Irredentism]] <br> | ||

|influenced = | |influenced = | ||

|preceded = | |preceded = | ||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

|school = | |school = | ||

|regional = | |regional = | ||

|song = | |song = [https://youtu.be/MBZ4q2y9mLE ekspansjówka - piosenka o irredentyźmie] | ||

|book = | |book = | ||

|movie = | |movie = | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

Polish irredentism encompasses the belief that certain territories not currently under Polish jurisdiction have historical, ethnic, or legal ties to Poland and should be reclaimed. This sentiment presents a range of claims and ideal borders, with variations dependent on individual perspectives. These claims can be broadly categorized into several prevailing concepts. The "Kresy Idea" centers on eastern territories, invoking the term "kresy" in Polish which translates to "borderlands." The "Recovered Territory Idea" pertains to regions such as Pomerania, Lubusz, and Silesia, with a focus on maintaining control of these areas in opposition to German irredentism. The "Saxony Claim" draws connections to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its historical links. The "Cieszyn Reunification" emphasizes the Czech side of the Cieszyn area. The "Western Pomeranian Reunification" advocates for areas like Griefswald that were once part of the Pomerania province. The "Polabian Idea" underscores the Polish-Polabian historical connection. The "Curonian Legacy" invokes Polish claims on territories such as Latvia, Tobago, and Gambia, reflecting the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's historical presence. Lastly, the "Madagascar Claim" addresses Polish historical interests in Madagascar. | Polish irredentism encompasses the belief that certain territories not currently under Polish jurisdiction have historical, ethnic, or legal ties to Poland and should be reclaimed. This sentiment presents a range of claims and ideal borders, with variations dependent on individual perspectives. These claims can be broadly categorized into several prevailing concepts. The "Kresy Idea" centers on eastern territories, invoking the term "kresy" in Polish which translates to "borderlands." The "Recovered Territory Idea" pertains to regions such as Pomerania, Lubusz, and Silesia, with a focus on maintaining control of these areas in opposition to German irredentism. The "Saxony Claim" draws connections to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its historical links. The "Cieszyn Reunification" emphasizes the Czech side of the Cieszyn area. The "Western Pomeranian Reunification" advocates for areas like Griefswald that were once part of the Pomerania province. The "Polabian Idea" underscores the Polish-Polabian historical connection. The "Curonian Legacy" invokes Polish claims on territories such as Latvia, Tobago, and Gambia, reflecting the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's historical presence. Lastly, the "Madagascar Claim" addresses Polish historical interests in Madagascar. | ||

==Kresy Idea== | ==[[File:KresyIdea.png]] Kresy Idea [[File:PolIrd.png]]== | ||

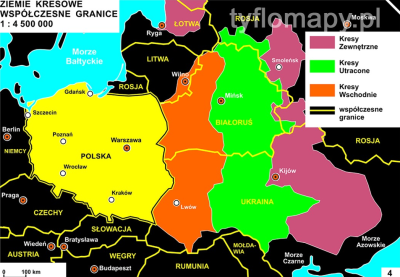

[[File:Kresy map.png|400px|thumb|left|Map of the 3 iterations of the Kresy]]<br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | [[File:Kresy map.png|400px|thumb|left|Map of the 3 iterations of the Kresy]]<br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br><br> | ||

The concept of the Kresy idea, sometimes referred to as the Kresy myth or the Eastern Borderlands, exhibits variations across different voivodeships and regions within the Kresy, with each iteration stemming from its historical origins dating back to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In contemporary times, modern Irredentists predominantly associate the Kresy with the eastern Polish territories owned during the interwar period, often denoted as "Kresy Wschodnie" or the eastern borderlands. Claims over the Belarussian segment of the Kresy are often predicated on ethnic factors, particularly as many of the territories with Belarusian ownership have a majority Polish population. Similar considerations apply to the Lithuanian Kresy. Concerning the Ukrainian Kresy, arguments for Polish ownership pivot more on questioning the organic nature of the Ukrainian identity itself, positing it as a constructed identity by the Hapsburg Empire in the 1880s as part of geopolitical maneuvering. Additional justifications for Polish ownership encompass historical precedents, such as Lwów and its environs having been under Polish control for over 400 years, surpassing any other historical ownership. Another angle pertains to the post-1945 border adjustments, contending that the changes were illegitimate, although they were sanctioned by the Soviet Union, USA, UK, and the Polish puppet government; the Government in exile purportedly acceded to these changes under duress due to their diminished influence.<br> | The concept of the Kresy idea, sometimes referred to as the Kresy myth or the Eastern Borderlands, exhibits variations across different voivodeships and regions within the Kresy, with each iteration stemming from its historical origins dating back to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In contemporary times, modern Irredentists predominantly associate the Kresy with the eastern Polish territories owned during the interwar period, often denoted as "Kresy Wschodnie" or the eastern borderlands. Claims over the Belarussian segment of the Kresy are often predicated on ethnic factors, particularly as many of the territories with Belarusian ownership have a majority Polish population. Similar considerations apply to the Lithuanian Kresy. Concerning the Ukrainian Kresy, arguments for Polish ownership pivot more on questioning the organic nature of the Ukrainian identity itself, positing it as a constructed identity by the Hapsburg Empire in the 1880s as part of geopolitical maneuvering. Additional justifications for Polish ownership encompass historical precedents, such as Lwów and its environs having been under Polish control for over 400 years, surpassing any other historical ownership. Another angle pertains to the post-1945 border adjustments, contending that the changes were illegitimate, although they were sanctioned by the Soviet Union, USA, UK, and the Polish puppet government; the Government in exile purportedly acceded to these changes under duress due to their diminished influence.<br> | ||

Other, more radical manifestations of the Kresy idea irredentism indeed exist, notably encompassing concepts such as "kresy utracone," which translates to "Lost Borderlands," alluding to the eastern frontiers of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth post the Treaty of Andrusovo, and "kresy zewnętrzne," or "Exterior Borderlands," signifying the eastern borders after the Truce of Deulino. The arguments advocating for the ownership of these territories are less prevalent, often entwined with imperialistic aspirations for the civilization of the East and similar national schizophrenias. The thesis of the inorganic nature of Ukraine's identity can also be extended to the southern territories of kresy zewnętrzne and kresy utracone. | Other, more radical manifestations of the Kresy idea irredentism indeed exist, notably encompassing concepts such as "kresy utracone," which translates to "Lost Borderlands," alluding to the eastern frontiers of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth post the Treaty of Andrusovo, and "kresy zewnętrzne," or "Exterior Borderlands," signifying the eastern borders after the Truce of Deulino. The arguments advocating for the ownership of these territories are less prevalent, often entwined with imperialistic aspirations for the civilization of the East and similar national schizophrenias. The thesis of the inorganic nature of Ukraine's identity can also be extended to the southern territories of kresy zewnętrzne and kresy utracone. | ||

==Recovered territory Idea== | ==[[File:RecTerr.png]] Recovered territory Idea [[File:PolIrd.png]]== | ||

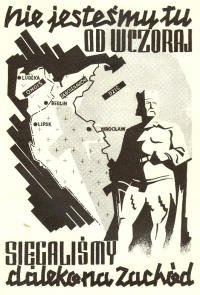

==Saxony claim== | [[File:Recovered Territories Propaganda.png|200px|thumb|left|propaganda from the 1930s about the western territories (Both Recovered territories and Polabian Idea)]] | ||

==Cieszyn Reunification== | The Recovered Territories, alternatively known as the Western Borderlands or Regained Lands, pertain to the former eastern territories of Germany and the Free City of Danzig that were assimilated into Poland following World War II. This successful implementation of irredentism took place in 1945, resulting in Poland acquiring substantial territories from Germany, even those without a predominant Polish ethnic majority. The displacement of the German populace occurred, leading to the polonization of these territories. Prior to the border alteration, the foundation for Polish ownership of these lands rested upon two main aspects. Firstly, a historical rationale was presented, highlighting that these lands were historically governed by the Duchy of Poland and later the Kingdom of Poland under various dynasties. This control persisted even after the Holy Roman Empire took possession of these territories subsequent to the Piast collapse. Notably, Silesia was ruled by Polish dynasties until being eventually taken by the Habsburgs and Pomerania was ruled by the Polish-Kashubian Gryf dynasty until it was partitioned by Prussia and Sweden. Secondly, an ethnic argument emerged, applicable to Upper Silesia, Warmia, and Masuria, where a majority of the population was ethnically Polish within Germany. Today, while the historical basis endures, the ethnic argument has been extended to encompass the entirety of the Recovered Territories. Moreover, Poland's substantial development of these regions since 1945 further justifies its claim to ownership. | ||

==Western Pomerania Reunification== | ==[[File:PolSax.png]] Saxony claim [[File:PolIrd.png]]== | ||

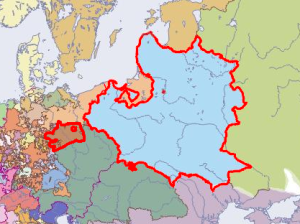

[[File:Poland-Saxony.png|300px|thumb|left|Lands ruled by Augustus II the Strong]] | |||

The Saxony Claim posits that Poland possesses a valid legal entitlement to the region of Saxony based on the historical premise that Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III jointly ruled over both the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Electorate of Saxony. This shared governance underscores the historical interconnectedness of Poland and Saxony. Additionally, the claim draws attention to the subsequent events involving Polish succession after Augustus III, notably with Stanisław II August, which resulted in the partitioning of the Commonwealth. This partition, driven by Stanisław II August's close connections with Russia, is considered by proponents of the Saxony Claim as an unjust and illegitimate outcome. Advocates contend that had the succession followed a different path, specifically with Frederick Christian's rule succeeding Augustus III, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Saxony could have potentially remained united and averted the partitions. It's important to note that the Saxony Claim is a topic mostly explored in alternate history contexts and is generally not regarded as a serious geopolitical contention and is often referenced as a point of discussion or debate rather than a concrete diplomatic argument. | |||

==[[File:CieReuni.png]] Cieszyn Reunification [[File:PolIrd.png]]== | |||

[[File:Zaolzie.png|250px|thumb|left|"For 600 years we have been waiting for you (1335–1938)." Ethnic Polish band welcoming the annexation of Zaolzie by the Polish Republic]] | |||

The Cieszyn Reunification concept advocates for the potential annexation of the Czech side of Cieszyn, including the broader Zaolzie region, into Poland. Originally grounded in ethnic considerations during the interwar period, given the city's majority Polish population, the current proposition maintains an ethnic foundation although demographic changes over time have led to a reduction in the percentage of Poles residing there. Alongside the ethnic basis, a historical claim has emerged due to Poland's prior ownership of the area from 1938 to 1939. Notably, the city's enduring Polish majority throughout its history, until recent times, underscores the role of Polish development and contributions to its growth, thus forming a basis for Poland's potential claim to the region. | |||

==[[File:WestpomReu.png]] Western Pomerania Reunification [[File:PolIrd.png]]== | |||

[[File:Pomerania map.png|197px|thumb|left|Map of Pomerania as a whole]] | |||

The Western Pomerania Reunification notion rests upon two primary arguments: a legal basis and a historical foundation. Legally, proponents contend that Poland assumed jurisdiction over Pomerania upon its annexation in 1945, thus asserting its rightful authority over the westernmost portion around Greifswald, presently situated within the state of Mecklenburg. Advocates assert that for Pomerania to be reunified, this region should be integrated into the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, which administers Szczecin and holds the legitimate Pomeranian succession. As the West Pomeranian Voivodeship is within Poland, the area of Greifswald should accordingly be incorporated into Poland. Historically, the argument parallels that applied to the wider concept of the Recovered Territories, emphasizing the historical affiliation of the Duchy of Pomerania with the Kashubian-Polish Gryf dynasty's rule. This historical continuity, persisting until its partition by Sweden and Prussia, underscores Poland's legitimate claim over Pomerania, including its modern German territories. The historic Kashubian ethnic majority in Pomerania until the Ostsiedlung is mentioned, though its application as an argument is limited due to the temporal distance of this event, dating back to 1181, and the subsequent cultural shifts. | |||

==Polabian Idea== | ==Polabian Idea== | ||

[[File:Polabs.png|135px|thumb|left|Map of Polabian and Sorbian tribes]] | |||

The Polabian idea posits that, akin to the historical and contemporary association of the Kashubians and Silesians with the Lechitic cultural group, the Polabians, and their modern counterparts, the Sorbians, also belong to this Lechitic heritage. This premise leads to the assertion that Poland, as the representative state of the Lechites, possesses a claim to the former Polabian territories that extended from the contemporary Polish-German boundary to the Elbe River that were colonized by German settlers. The concept of the Polabian Idea finds its predominant application within alternate history narratives, Panslavist circles, and scenarios or plans envisioning potential partitions of Germany. | |||

==Curonian Legacy== | ==Curonian Legacy== | ||

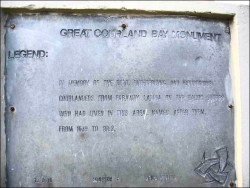

[[File:CourlandBayMonument.png|250px|thumb|left|Great Courland Bay Monument]] | |||

The Curonian Legacy concept represents a manifestation of Polish neo-colonialism and centers around the historical Duchy of Courland, which was a vassal state within the realm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The central argument postulates that due to its subordinated status under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Duchy of Courland should be regarded as an integral part of that historical entity. Consequently, the colonies under Curonian administration, namely Tobago and Gambia, ought to be viewed as territories colonized and governed by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its subsequent successors, Poland and Lithuania, rather than by the Courland successor, Latvia.<br> | |||

This idea contends that Poland stands as the rightful heir to the ownership of these colonies, as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's administration and ethnic composition were predominantly Polish. This perspective strengthens Poland's claim as the legitimate successor to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth compared to Lithuania. An additional argument supporting this notion is rooted in Lithuania's post-World War I pursuit of independence, which involved a rejection of the Polish-Lithuanian identity, accompanied by a contentious perspective on the historical Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In contrast, Poland has embraced its role as the successor to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth since gaining independence after World War I, maintaining a positive view of its historical legacy and policies associated with it.<br> | |||

The Curonian Legacy idea was notably prominent within [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maritime_and_Colonial_League the Maritime and Colonial League] during the interwar period. This league advocated for the Second Polish Republic to establish its own colonial endeavors. In contemporary times, the concept has diminished in popularity due to the decline of colonialism as a practiced phenomenon. Nevertheless, proponents of neo-colonialism still endorse the notion of Polish ownership of these territories, grounding their support in the historical arguments outlined by this perspective. | |||

==Madagascar Claim== | ==Madagascar Claim== | ||

[[File:Autonomous region of western madagascar.png|160px|thumb|left|Imagine from an APR 01 2008 satirical article by POLANDIAN about Poland being given parts of western Madagascar ]] | |||

The Polish assertion of a claim to Madagascar originates from the historical expeditions led by Maurice Benyovszky to the island during the late 18th century. While the accounts of these ventures are limited and contradictory, they have given rise to a Polish perspective on the sequence of events. According to this perspective, Benyovszky successfully persuaded the French Foreign Minister d'Aiguillon and Navy Secretary de Boynes in Paris to finance an expedition aimed at establishing a French colony on Madagascar. This endeavor, which commenced in November 1773, culminated in the full establishment of the colony by March 1774. The colony established a trading post at Antongil on the island's eastern coast and initiated negotiations with the local population for various resources.<br> | |||

Records indicate that the region's inhabitants proclaimed Benyovszky as their supreme chief and king (Ampansacabe). Following Benyovszky's departure from the colony—whether permanently or temporarily remains uncertain—the remaining 'Benyovszky Volunteers' were disbanded in May 1778. Subsequently, the French government ordered the dismantling of the trading post in June 1779. Many observers characterize Benyovszky's kingdom as a Polish-Hungarian colony under French influence, rather than a purely French colony. This interpretation is supported by two factors: first, the locals recognized Benyovszky as their supreme chief and king, establishing a feudal hierarchy under the French Empire; second, the eventual dissolution of the colony against Benyovszky's presumed wishes cultivated a desire for independence and distinct interests from the French mainland or other parts of French Madagascar.<br> | |||

This narrative of a Polish-Hungarian Madagascar persisted due to the efforts of the Maritime and Colonial League, which proposed the purchase of Madagascar from the French Empire, drawing on the aforementioned historical account. The plan gained significant traction within the Polish populace, driven in part by the 1937 visit of renowned Polish writer Arkady Fiedler to the town of Ambinanitelo in Madagascar. Fiedler's prolonged stay and subsequent book detailing the local culture resonated deeply with the Polish public.<br> | |||

The concept of making Madagascar a Polish colony also coincided with proposals to encourage Jewish emigration from Poland. The Polish government even approached the League of Nations in 1936 with the idea of using Madagascar as a resettlement destination for the perceived surplus Jewish population. A delegation was dispatched to Madagascar in 1937 to assess its feasibility. France participated in this venture as well, aiming to enhance its ties with Poland and deter potential cooperation between Poland and Germany. However, the outbreak of the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 effectively halted these plans.<br> | |||

In contemporary times, the notion of Poland owning Madagascar has waned, although Madagascar remains a noteworthy element in Polish popular culture. It is acknowledged as basically the sole African nation to have experienced substantial Polish influences, evidenced by street names honoring both Maurice Benyovszky and Arkady Fiedler. A unique Polish organization, the POLka Association, established in 2006, operates within the Nairobi consular district of Madagascar. Additionally, while the idea of a Polish-controlled Madagascar is not prevalent today, it garners significant attention within the realm of alternate history enthusiasts. | |||

Latest revision as of 16:02, 19 June 2024

Polish irredentism encompasses the belief that certain territories not currently under Polish jurisdiction have historical, ethnic, or legal ties to Poland and should be reclaimed. This sentiment presents a range of claims and ideal borders, with variations dependent on individual perspectives. These claims can be broadly categorized into several prevailing concepts. The "Kresy Idea" centers on eastern territories, invoking the term "kresy" in Polish which translates to "borderlands." The "Recovered Territory Idea" pertains to regions such as Pomerania, Lubusz, and Silesia, with a focus on maintaining control of these areas in opposition to German irredentism. The "Saxony Claim" draws connections to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its historical links. The "Cieszyn Reunification" emphasizes the Czech side of the Cieszyn area. The "Western Pomeranian Reunification" advocates for areas like Griefswald that were once part of the Pomerania province. The "Polabian Idea" underscores the Polish-Polabian historical connection. The "Curonian Legacy" invokes Polish claims on territories such as Latvia, Tobago, and Gambia, reflecting the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's historical presence. Lastly, the "Madagascar Claim" addresses Polish historical interests in Madagascar.

Kresy Idea

Kresy Idea

The concept of the Kresy idea, sometimes referred to as the Kresy myth or the Eastern Borderlands, exhibits variations across different voivodeships and regions within the Kresy, with each iteration stemming from its historical origins dating back to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In contemporary times, modern Irredentists predominantly associate the Kresy with the eastern Polish territories owned during the interwar period, often denoted as "Kresy Wschodnie" or the eastern borderlands. Claims over the Belarussian segment of the Kresy are often predicated on ethnic factors, particularly as many of the territories with Belarusian ownership have a majority Polish population. Similar considerations apply to the Lithuanian Kresy. Concerning the Ukrainian Kresy, arguments for Polish ownership pivot more on questioning the organic nature of the Ukrainian identity itself, positing it as a constructed identity by the Hapsburg Empire in the 1880s as part of geopolitical maneuvering. Additional justifications for Polish ownership encompass historical precedents, such as Lwów and its environs having been under Polish control for over 400 years, surpassing any other historical ownership. Another angle pertains to the post-1945 border adjustments, contending that the changes were illegitimate, although they were sanctioned by the Soviet Union, USA, UK, and the Polish puppet government; the Government in exile purportedly acceded to these changes under duress due to their diminished influence.

Other, more radical manifestations of the Kresy idea irredentism indeed exist, notably encompassing concepts such as "kresy utracone," which translates to "Lost Borderlands," alluding to the eastern frontiers of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth post the Treaty of Andrusovo, and "kresy zewnętrzne," or "Exterior Borderlands," signifying the eastern borders after the Truce of Deulino. The arguments advocating for the ownership of these territories are less prevalent, often entwined with imperialistic aspirations for the civilization of the East and similar national schizophrenias. The thesis of the inorganic nature of Ukraine's identity can also be extended to the southern territories of kresy zewnętrzne and kresy utracone.

Recovered territory Idea

Recovered territory Idea

The Recovered Territories, alternatively known as the Western Borderlands or Regained Lands, pertain to the former eastern territories of Germany and the Free City of Danzig that were assimilated into Poland following World War II. This successful implementation of irredentism took place in 1945, resulting in Poland acquiring substantial territories from Germany, even those without a predominant Polish ethnic majority. The displacement of the German populace occurred, leading to the polonization of these territories. Prior to the border alteration, the foundation for Polish ownership of these lands rested upon two main aspects. Firstly, a historical rationale was presented, highlighting that these lands were historically governed by the Duchy of Poland and later the Kingdom of Poland under various dynasties. This control persisted even after the Holy Roman Empire took possession of these territories subsequent to the Piast collapse. Notably, Silesia was ruled by Polish dynasties until being eventually taken by the Habsburgs and Pomerania was ruled by the Polish-Kashubian Gryf dynasty until it was partitioned by Prussia and Sweden. Secondly, an ethnic argument emerged, applicable to Upper Silesia, Warmia, and Masuria, where a majority of the population was ethnically Polish within Germany. Today, while the historical basis endures, the ethnic argument has been extended to encompass the entirety of the Recovered Territories. Moreover, Poland's substantial development of these regions since 1945 further justifies its claim to ownership.

Saxony claim

Saxony claim

The Saxony Claim posits that Poland possesses a valid legal entitlement to the region of Saxony based on the historical premise that Augustus II the Strong and Augustus III jointly ruled over both the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Electorate of Saxony. This shared governance underscores the historical interconnectedness of Poland and Saxony. Additionally, the claim draws attention to the subsequent events involving Polish succession after Augustus III, notably with Stanisław II August, which resulted in the partitioning of the Commonwealth. This partition, driven by Stanisław II August's close connections with Russia, is considered by proponents of the Saxony Claim as an unjust and illegitimate outcome. Advocates contend that had the succession followed a different path, specifically with Frederick Christian's rule succeeding Augustus III, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Saxony could have potentially remained united and averted the partitions. It's important to note that the Saxony Claim is a topic mostly explored in alternate history contexts and is generally not regarded as a serious geopolitical contention and is often referenced as a point of discussion or debate rather than a concrete diplomatic argument.

Cieszyn Reunification

Cieszyn Reunification

The Cieszyn Reunification concept advocates for the potential annexation of the Czech side of Cieszyn, including the broader Zaolzie region, into Poland. Originally grounded in ethnic considerations during the interwar period, given the city's majority Polish population, the current proposition maintains an ethnic foundation although demographic changes over time have led to a reduction in the percentage of Poles residing there. Alongside the ethnic basis, a historical claim has emerged due to Poland's prior ownership of the area from 1938 to 1939. Notably, the city's enduring Polish majority throughout its history, until recent times, underscores the role of Polish development and contributions to its growth, thus forming a basis for Poland's potential claim to the region.

Western Pomerania Reunification

Western Pomerania Reunification

The Western Pomerania Reunification notion rests upon two primary arguments: a legal basis and a historical foundation. Legally, proponents contend that Poland assumed jurisdiction over Pomerania upon its annexation in 1945, thus asserting its rightful authority over the westernmost portion around Greifswald, presently situated within the state of Mecklenburg. Advocates assert that for Pomerania to be reunified, this region should be integrated into the West Pomeranian Voivodeship, which administers Szczecin and holds the legitimate Pomeranian succession. As the West Pomeranian Voivodeship is within Poland, the area of Greifswald should accordingly be incorporated into Poland. Historically, the argument parallels that applied to the wider concept of the Recovered Territories, emphasizing the historical affiliation of the Duchy of Pomerania with the Kashubian-Polish Gryf dynasty's rule. This historical continuity, persisting until its partition by Sweden and Prussia, underscores Poland's legitimate claim over Pomerania, including its modern German territories. The historic Kashubian ethnic majority in Pomerania until the Ostsiedlung is mentioned, though its application as an argument is limited due to the temporal distance of this event, dating back to 1181, and the subsequent cultural shifts.

Polabian Idea

The Polabian idea posits that, akin to the historical and contemporary association of the Kashubians and Silesians with the Lechitic cultural group, the Polabians, and their modern counterparts, the Sorbians, also belong to this Lechitic heritage. This premise leads to the assertion that Poland, as the representative state of the Lechites, possesses a claim to the former Polabian territories that extended from the contemporary Polish-German boundary to the Elbe River that were colonized by German settlers. The concept of the Polabian Idea finds its predominant application within alternate history narratives, Panslavist circles, and scenarios or plans envisioning potential partitions of Germany.

Curonian Legacy

The Curonian Legacy concept represents a manifestation of Polish neo-colonialism and centers around the historical Duchy of Courland, which was a vassal state within the realm of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The central argument postulates that due to its subordinated status under the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the Duchy of Courland should be regarded as an integral part of that historical entity. Consequently, the colonies under Curonian administration, namely Tobago and Gambia, ought to be viewed as territories colonized and governed by the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and its subsequent successors, Poland and Lithuania, rather than by the Courland successor, Latvia.

This idea contends that Poland stands as the rightful heir to the ownership of these colonies, as the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth's administration and ethnic composition were predominantly Polish. This perspective strengthens Poland's claim as the legitimate successor to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth compared to Lithuania. An additional argument supporting this notion is rooted in Lithuania's post-World War I pursuit of independence, which involved a rejection of the Polish-Lithuanian identity, accompanied by a contentious perspective on the historical Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. In contrast, Poland has embraced its role as the successor to the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth since gaining independence after World War I, maintaining a positive view of its historical legacy and policies associated with it.

The Curonian Legacy idea was notably prominent within the Maritime and Colonial League during the interwar period. This league advocated for the Second Polish Republic to establish its own colonial endeavors. In contemporary times, the concept has diminished in popularity due to the decline of colonialism as a practiced phenomenon. Nevertheless, proponents of neo-colonialism still endorse the notion of Polish ownership of these territories, grounding their support in the historical arguments outlined by this perspective.

Madagascar Claim

The Polish assertion of a claim to Madagascar originates from the historical expeditions led by Maurice Benyovszky to the island during the late 18th century. While the accounts of these ventures are limited and contradictory, they have given rise to a Polish perspective on the sequence of events. According to this perspective, Benyovszky successfully persuaded the French Foreign Minister d'Aiguillon and Navy Secretary de Boynes in Paris to finance an expedition aimed at establishing a French colony on Madagascar. This endeavor, which commenced in November 1773, culminated in the full establishment of the colony by March 1774. The colony established a trading post at Antongil on the island's eastern coast and initiated negotiations with the local population for various resources.

Records indicate that the region's inhabitants proclaimed Benyovszky as their supreme chief and king (Ampansacabe). Following Benyovszky's departure from the colony—whether permanently or temporarily remains uncertain—the remaining 'Benyovszky Volunteers' were disbanded in May 1778. Subsequently, the French government ordered the dismantling of the trading post in June 1779. Many observers characterize Benyovszky's kingdom as a Polish-Hungarian colony under French influence, rather than a purely French colony. This interpretation is supported by two factors: first, the locals recognized Benyovszky as their supreme chief and king, establishing a feudal hierarchy under the French Empire; second, the eventual dissolution of the colony against Benyovszky's presumed wishes cultivated a desire for independence and distinct interests from the French mainland or other parts of French Madagascar.

This narrative of a Polish-Hungarian Madagascar persisted due to the efforts of the Maritime and Colonial League, which proposed the purchase of Madagascar from the French Empire, drawing on the aforementioned historical account. The plan gained significant traction within the Polish populace, driven in part by the 1937 visit of renowned Polish writer Arkady Fiedler to the town of Ambinanitelo in Madagascar. Fiedler's prolonged stay and subsequent book detailing the local culture resonated deeply with the Polish public.

The concept of making Madagascar a Polish colony also coincided with proposals to encourage Jewish emigration from Poland. The Polish government even approached the League of Nations in 1936 with the idea of using Madagascar as a resettlement destination for the perceived surplus Jewish population. A delegation was dispatched to Madagascar in 1937 to assess its feasibility. France participated in this venture as well, aiming to enhance its ties with Poland and deter potential cooperation between Poland and Germany. However, the outbreak of the German invasion of Poland in September 1939 effectively halted these plans.

In contemporary times, the notion of Poland owning Madagascar has waned, although Madagascar remains a noteworthy element in Polish popular culture. It is acknowledged as basically the sole African nation to have experienced substantial Polish influences, evidenced by street names honoring both Maurice Benyovszky and Arkady Fiedler. A unique Polish organization, the POLka Association, established in 2006, operates within the Nairobi consular district of Madagascar. Additionally, while the idea of a Polish-controlled Madagascar is not prevalent today, it garners significant attention within the realm of alternate history enthusiasts.