Original language: German

Original publication: 30 January 1933

Written by: Karl Otto Paetel

Translated by: ARPLAN (Bogumil)

License of this version: CC0

Other language versions: N/A

Link to PDF: PDF

Other links: Internet Archive

CONTENTS

- Translator’s Introduction

- Cover

- Vision

- The Task

- Ten Years of ‘National Bolshevism’

- Young Nationalism

- Reformed National Socialism?

- The Fascist Mistake

- The Historical Error of the NSDAP

- Nationalist Communism

- The Face of National Communism

- Why Not KPD?

- War and Peace

- Happiness or Freedom?

- The Nation as the ‘Highest Value’

- Marxism and the National Question

- Rural Revolution?

- The Peasant Question in Germany

- Council-State or Corporate-State?

- Socialism

- Prussia as a Principle

- The Class Struggle as a Nationalist Demand

- Versailles

- Revolutionary Foreign Policy

- The New Faith

- The Order of the Nation

- Can Wait

Translator’s Introduction

On Paetel

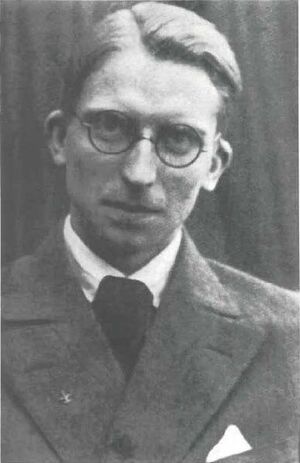

Karl Otto Paetel was born into a solidly middle-class Berlin-Charlottenberg family on November 23, 1906. The son of a bookseller, Paetel developed literary and intellectual interests early, and like most youth of his generation his thinking and outlook was deeply affected by the experience of the Great War and Germany’s subsequent post-War travails. The flourishing German Youth Movement, too, had a strong impact on his development – it was Paetel’s involvement in various youth groups that helped reinforce his nationalist sentiments, as well as his appreciation for the comradeship that came with activity within the framework of a tight-knit organization united around a common cause.

In 1928 Paetel enrolled at Friedrich-Wilhelm University in Berlin, studying philosophy and history with the intention of becoming a schoolteacher. Paetel’s studies were brought to an end only five semesters later as a result of his early forays into political activism. Defying a ban on demonstrations, a mass of students descended on the French Embassy in protest against the Treaty of Versailles, Paetel among them. To his shock he soon found himself slung in the back of a police vehicle, stuffed inbetween a Communist youth on one side and a National Socialist doctoral student on the other. The consequence of Paetel’s arrest once the University was alerted was the loss of his scholarship and his subsequent expulsion. With a sudden excess of free time on his hands, Paetel threw himself into journalism, writing articles for a variety of publications. He was particularly attracted to political subjects.

Paetel at this time was still also active within the Youth Movement; by this point in his life he had become a prominent figure within the hierarchy of the youth group Deutsche Freischar, an organization whose culture (initially, at least) complemented his own nationalist sentiments. As he became more politically active Paetel became much more strongly influenced by the ‘new nationalism’ popular at the time, a nationalism that positioned itself in the ‘revolutionary camp’ and rejected the stolidness of the old Wilhelmine era. Inspired by the work of figures such as Ernst Jünger, Ernst Niekisch, and August Winnig, Paetel’s writing adopted an increasingly radical tone, his nationalism becoming imbued with a strong undercurrent of anticapitalism. Yet as Paetel and his writing grew more radical, his position within the Deutsche Freischar became jeopardized. Paetel’s open sympathy for communism, his approving references to Lenin, his declaration that revolutionary young nationalists were the natural allies of the working-classes – these sentiments were a step too far for the Freischar. After writing an article in 1930 which criticized President Hindenburg over Germany’s ratification of the Young Plan, Paetel was forced to resign from his positions within the group.

In May 1930, an increasingly-radicalized Paetel decided to start taking serious political action. For a year he and a number of friends had been working within an informal group called the Young Front Working Circle, an advocacy organization which tried to rally left- and right-wing radicals to join together in common cause. Now Paetel and his comrades chose to reorganize themselves as a formal group with a formal program, seeking to do more than simply try and push members of the NSDAP towards ‘real socialism’. The ‘Group of Social-Revolutionary Nationalists’ (GSRN) they formed subsequently became one of the very few organizations in Weimar Germany which actually used the term ‘National Bolshevist’ to describe itself. Avowedly revolutionary, the GSRN advocated for the overthrow of the democratic-capitalist system, for a new government based on councils, for socialization of industry and land, for a military alliance with Soviet Russia, and for the arming of the masses as a Peoples’ Militia. The GSRN, whose members were, like Paetel, almost all of educated middle-class background, affirmed that it was the task of nationalists to work together with the classconscious proletariat in pursuit of these goals.

Despite this new sense of purpose, the initial focus of the GSRN – never a very large group – was on publishing and propaganda. An opportunity to engage in more lively action, however, was soon provided by the Left. A debate within the GSRN over whether to support the NSDAP or the KPD (Communist Party of Germany) in the September 1930 elections was suddenly resolved with the KPD’s publication of its new party programme, the ‘Programme for the National and Social Liberation of the German People’. This new programme was replete with nationalist language and demands, a deliberate attempt by the KPD to win back voters lost (or potentially lost) to the NSDAP. The GSRN however saw it as potential evidence that the KPD was drifting in a National Bolshevist direction, and so Paetel and his comrades threw their firm support behind the communists.

The GSRN thus became an ally of the KPD. Paetel and his group publicly supported the KPD during the election: writing articles, distributing propaganda, speaking at communist rallies. This cooperation continued on after the election, with the GSRN imploring nationalists to fight side-by-side with the KPD, declaring that only under the banners of communism would Germany be able to crush capitalism and liberate itself from the imperialism of the Versailles powers. GSRN members wrote articles for communist journals, joined KPD organizations like Antifascist Action, and in March and April 1932 they offered public support for the presidential campaign of KPD leader Ernst Thälmann. The KPD, for its part, provided its own form of support at times (such as by assisting in the distribution of the GSRN journal Socialist Nation), but overall the relationship was fairly one-sided.

It was this lack of reciprocity which led to a measure of disillusionment in the GSRN. Paetel came to suspect, quite rightly, that the KPD was hoping to co-opt and absorb his movement. Furthermore, by late 1932 he and his comrades had come to doubt the sincerity of the KPD’s nationalism. As KPDGSRN relations deteriorated, the ideological divisions between the two groups became more apparent; Paetel and his compatriots could no longer so easily wave away the fact that their end-goal of a nationalist-socialist sovereign German state, allied with but independent of a sovereign Soviet Russia, was fundamentally different to the ultimate goal of the KPD: borderless world communism. Although still pro-communist and supportive of the KPD, this division influenced the GSRN’s tactics, with Paetel attempting to organize a separate National Communist Party to compete in the November ’32 elections – an effort which failed due to the GSRN simply lacking the manpower and resources needed to bring forth a new legal political party.

The National Bolshevist Manifesto was published by Paetel as part of a second attempt to organize a National Communist electoral group, this time during the period in late 1932 to early 1933 when Germany was in a political shambles. The NSDAP was bleeding support, the KPD was gaining votes but struggling with internal factional disputes, and the entire Weimar system seemed on the verge of collapse. Yet events overtook Paetel in a fashion he had not predicted – the Manifesto he had laboured over was first published and distributed on January 30, 1933, the day Hitler became Chancellor and victorious, torch-bearing Stormtroopers marched in massed columns through the streets of Berlin. Many of the copies of the Manifesto were confiscated and pulped, Paetel’s publication license was swiftly withdrawn, and the publications of he and his comrades were shut down. The GSRN did not last much longer, being banned along with the other communist and ‘fellow-traveller’ groups in the aftermath of the Reichstag fire.

From that point onwards Paetel experienced significant harassment from the government, particularly as he continued to associate with figures considered unsavoury to the National Socialist regime. His name was included on a black-list of suspected traitors during the events of the June 1934 Blood Purge (the ‘Night of the Long Knives’), and by 1935 things had become so heated that Paetel was forced to flee Germany for his own safety. After some time moving around Europe he ended up in America, where he managed to find employment as an academic and eventually attained citizenship. In his later life Paetel published a number of different works, several of them detailing the history of German National Bolshevism. He died in New York in 1975.

On the Translation

This translation was made over the course of several months from early- to mid-2019. From the next page onwards everything, as far as is possible, is a replica in terms of content and style of Paetel’s original National Bolshevist Manifesto. All the numbered footnotes within the text (i.e. 1 2 3) are Paetel’s, translated from the original German. The only change that has been made to them is put some of them into order – whether due to a printing error or complications in formatting and layout, the German version of the Manifesto does not order all the footnotes sequentially: the details for footnote 59, for instance, are preceded by footnote 60 and followed by footnote 58. For the sake my sanity and that of the readers, I have fixed this for the English translation.

Paetel in the Manifesto makes extensive reference to newspapers, journals, books, and articles. Most of the original newspapers and journals Paetel references have had their German names left untranslated to make their identification easier (Paetel’s own frequently-appearing Sozialistische Nation is the one exception – I have consistently used the English translation Socialist Nation instead). Books and articles have had their names translated to make their contents more apparent to the reader, but the original German names are provided in brackets and Italics [“like so”] for anyone interested in tracking them down. The only works I have avoided this with are those which are already widely-known in English-speaking countries, such as those of Marx, Lenin, Trotsky, Jünger, etc.

At times in the text I have included the original German for a word or phrase alongside the English translation, [like this]. This has mainly been employed when translating striking or unusual expressions – typically völkisch language, which does not always have an easy, direct translation in English. The only other additions I have made to the text are my own Translator’s Notes. These are indicated in the text using footnote symbols (i.e. *†‡§) to make them easily distinguishable from Paetel’s numbered footnotes – the numbers are Paetel’s, the symbols are mine. Sometimes these notes are employed to provide detail on a translating choice, more commonly they are there to offer some historical background to the reader. Much of Paetel’s Manifesto is concerned with discussing and dissecting the ideas and writings of his political and cultural contemporaries, and he additionally makes frequent literary allusions and references to German historical events. This all has the potential of being rather obscure to modern, 21st century, English-speaking readers; Paetel assumes that his readers will of course know (for example) who “the communist Thomas” was or what “the slogan of the 97%” is in reference to, but this is less likely today than it was in 1933. I have endeavoured to be as neutral as possible in these sections, since one thing I despise is an editor or translator trying to influence my opinion on a text. Regardless, I am aware that these notes are my own work and not Paetel’s original, that people have downloaded this document to read Paetel’s words and not my own, so I have also attempted to make the separation as clear as possible. The Translator’s Notes sections are very clearly indicated at the end of the relevant chapters with a heading and a different font, and I have deliberately tried to make them as small and unobtrusive as possible. If people find them distracting or unnecessary then I will happily issue an edition of the translation without them.

I hope you enjoy this work. Please feel free to distribute it where you like. If you have access to the German original (there are PDF copies available online; I used a physical reprint from German publishers Haag & Herchen) and believe you can improve the translation, then also please feel free to do so. The most important thing is that Paetel’s writings are available – I have no special claim over them. If you have any questions, criticisms, or suggestions, please feel free to contact me.

arplan.org

Cover

The National Bolshevist Manifesto

A.K.

Dedicated to my good comrade.

New tablets bear the writ of the new age: Let greybeards revel in their heritage; The distant thunder does not reach their ears. But you shall label all the young ones lackeys Who drug themselves on mushy music now, Who skirt with chains of roses the abyss. You shall spit out what’s decadent and rotten And hide the dagger in the laurel wreath, – Tuned to the new crusade in step and sound.

Stefan George, 1913.

These simple phrases of Moeller van den Bruck should be of service to these pages. – Even where they go beyond them. No “refutation” of any “ism”, no academic work. – Only in the clearcut distinction of the fronts – self-understanding – for a young race that wants at any price:

Even if this price means:

Breaking with yesterday!

So we take up that dirty phrase:

“National Bolsheviks!”

Karl O. Paetel

On the day of the ‘historical torchlight procession’,

30th January 1933

“There is no German Reich, there is no German government, there is no German representation, there is only a colony of the Entente. We are natives of a colony. That’s the entire cruel and unrelenting truth, which one must make peace with mentally before thinking ahead.”

(From the “Vörwarts” of 15 May, 1919.)

Vision

The red flag flutters over Cologne Cathedral.

Revolution over Germany. – –

Radiogram from Berlin:

“To the German people! Land and soil belong to the nation. The means of production are socialized. Elections to the Council Congress are announced. The verdicts of the People’s Court on all the enemies of the Socialist Fatherland, all those responsible for the old regime, are enforced. The Treaty of Versailles is considered torn to pieces. Greater Germany is socialist! The imperialist bandit-states are approaching. The Rhine is to be held under all circumstances, the counter-attack is to be initiated!”

– – – Long columns, black on black, trek across the Rhine bridges.

Singing rings out.

Flags wave in rhythm with the tramp of marching feet.

Columns of workers, rifles shouldered; in their midst flags with the hammer and sickle. The bars of the Marseillaise – – “The Fatherland is in danger!” – – A short distance behind them come streamlined figures in brown shirts, above their heads the red swastika banner, and over that a red pennant with the symbols of labour, their armbands half-covered with red strips.

A new column, grey on grey, endless troops of the Stahlhelm behind the war flags of the Great War of 1914-1918, their flags also bedecked with the red pennant of the revolutionary uprising, and peasant formations beyond them.

And luminescent above all the flags, over red, black-white-red, and black banners, raising its wings, the black eagle of Prussia!

Singing roars through the columns of the army, and the chorus is always growing stronger, and all the troops take it up, grey, brown and red formations coming in:

“To the Rhine, to the Rhine,

To the German Rhine,

Guardians we all want to be!”

And a shout sounds out:

“Long live socialism!

We carry the red flags under the German eagle

Into France!

Forwards!”

The voice breaks off. – Only the masses march. Endless. With different flags, in different dress, in the same step. Marching in enemy territory. Suppressed freedom, bringing the Lord’s retribution for a life of human bondage.

– – – –

This is the gateway to tomorrow. The way to it? The way we are!

The Task

Germany has to fight today for the freedom of its unfree-born children, for a future home for its homeless, for the future hopeless generations.

But not only that. In German territory will the vision of our century be shaped. Here shall the formal principle of Mitteleuropa* have to be proven. The fight for the sovereignty of the German lands will decide the fight for Europe’s future, the rise or fall of the West. In German hearts and German minds today the forces of the East are already feuding with the principles of Western thought. The solution will have to be: to find one’s own principle.

In the body of the German people [deutschen Volkskörper], within the German territories, the decisive battle will be fought between world mercantilist economy and socialist statehood. Here the class struggle between proletarian dynamism and bourgeois self-reliance will be fulfilled.1

The task that lies before the young generation of political Germans is one of decades. To solve it means giving a new, creative meaning to that old misused concept of the German imperial world-mission2 ; that on the third attempt (Moeller van den Bruck’s expression already carries this meaning) the German nation-building which was unsuccessful in the Ottonenreich and Staufferreich, as well as in the Bismarckian Reich† , will become a reality.

To break away from this task means gambling away the future of Eternal Germany, shifting the Switzerlandization‡ of the German Volk into its final stage.

The name of the task is, becoming a Nation.3

Its guarantor is called, Socialism.

The path to it: Revolution.

Only those called to this task from within will understand what it is about, alone and above all: to open the door to tomorrow for a proletarianized Volk; to break all its bonds – chaos, adversity, affirmation of victimhood, class, estate, granting it personal happiness – in order that reality for the German people shall be:

The nation as the highest value.

1 This has nothing to do with hazy ‘Reich’ fantasies in the style of Youth Movement romanticism or the intellectual exercises§ of the ‘Mitteleuropa’-ideologists – both today drift off into idealism.

2 Even Lenin says in “Left-Wing” Communism: an Infantile Disorder: “It would, of course, be grossly erroneous to exaggerate this truth and extend it beyond certain fundamental features of our revolution. It would also be erroneous to lose sight of the fact that, soon after the victory of the proletarian revolution in at least one of the advanced countries, a sharp change will probably come about: Russia will cease to be the model and will once again become a backward country (in the "Soviet" and the socialist sense).”

3 The popular misrepresentation of the concepts Race – Volk – Nation must finally be brought to an end. From racial and other indiscernible elements arose the Volk. The Nation, as the historical form of this biological fact that emerges into the consciousness of the folk-comrades [Volksgenossen], still has yet to arise in Germany; the task of socialism is to create a Nation out of the mass and “populace” of the Volk, or, as Hegel would phrase it, for the “people in themselves” to become the “people for themselves”. There is therefore something inadequate in the definition given by Bortoletto (Fascism and Nation, Hamburg): “The Nation is a historical and biological concept, it is a unified, enduring, and indivisible entity of perfect existence, a truly autonomous social or political body.”

Translator’s Notes

* The Mitteleuropa (‘Central Europe’) concept Paetel refers to here was discussed in German-speaking lands from the mid19th century onwards, proposing the idea of central-European federation, empire, or trading bloc as a counterbalance to the Western powers on one hand, and the Russian Empire on the other. In most conceptions of the idea, such as Friedrich Naumann’s 1915 work by the same name (Naumann himself was the progenitor of an early, prototypical form of nationalistsocialism), the Mitteleuropa power bloc would naturally be led by Germany or Austria.

† “Ottonenreich” and “Staufferreich” are alternative terms for the Ottonian and Hohenstaufen dynasties of the Holy Roman Empire respectively. “Moeller van den Bruck’s expression” is a reference to the concept of the ‘Third Reich’, an ideal popular not just with the National Socialists but among nationalists of all stripes. Arthur Moeller van den Bruck, one of the most influential conservative-revolutionary intellectuals, is typically credited with popularizing the concept of the Third Reich, if not inventing it.

‡ The German word used here is ‘Verschweizerung’, which in English could be rendered as ‘Switzerlandization’ or ‘Swissification’. In 1928, völkisch journalist Hans von Liebig wrote a book called The Switzerlandization of the German Peoples [“Die Verschweizerung des deutschen Volkes”] which is possibly what Paetel is invoking by his use of the term. Switzerlandization, as von Liebig described it, is the process of a nation taking on the qualities of Switzerland, i.e. becoming a multi-ethnic society, peopled by different ethnic minorities with different languages and different cultures, all living sideby-side, without any real national sense uniting them.

§ ‘Intellectual exercises’ – The actual German word Paetel uses here is ‘Schreibtischrezepten’, which literally translates as ‘writing-desk recipes’.

Ten Years of ‘National Bolshevism’

Wherever in Young-Germany* today the deathly stillness of official politics is alarmed by an underground tremor – wherever the unconditionality of nationalist youth calls into question the old values of their fathers, over whose funeral-shrouds the elderly wail with spread hands, registering the (still emotional) socialist demand of the national-revolutionary young bourgeoisie – wherever the proletariat seems to recognize that only the German eagle on red flags will create a Fatherland for them which bears the national fervour of those without a Homeland - there does one see in the bourgeois newspapers a watchword:

National Bolshevism!

But what historical fact first arose in Germany to trigger the political movement meant by that phrase?

It is not enough simply to take a pro-Russia-policy as its criterion, to see in it simply nothing but foreign policy- not at all. Its conception of foreign policy is indeed only the self-evident result of a very basic assessment.

The first truly National Bolshevist document was the ‘Political Testament’ of Count Brockdorff-Rantzau, 4 in which he set down the belief that a German radical socialism must take in hand, beneath the banners of socialism, a policy of freedom against Western imperialism and capitalism.5

Brockdorff-Rantzau’s† refusal to sign the Treaty of Versailles, Lenin’s offer to the People’s Deputies to support the resistance on the Rhine – these were the political realities behind it.6 The second National Bolshevist wave was the policy of fraternization pursued by the Hamburg ‘National-Communist circles’ under Wolffheim-Laufenberg‡ (alongside and within the KAPD, after their expulsion from the KPD), with parts of General Lettow-Vorbeck’s Freikorps in Hamburg and other cities. Later there were the efforts in Munich to come to a policy of joint action between the communist Thomas, völkisch Police-President Poehner§ , and the fellows of the Freikorps Oberland7 , attempting such organising in Thuringia, in the East Prussian border-guard, and yes, among the Kapp soldiers.8

Writings such as Wolffheim’s “Nation and Working Class”, a dissertation against the methods in Russia titled “Moscow and the German Revolution”, the “Open Letter to Major-General Lettow-Vorbeck: Communism – A National Imperative” by Judicial Councillor Krüpfgantz**, among others – these were the ideological weapons with which those within the circles of the Communist Party and the right-wing radical groups campaigned for this synthesis. The Hamburger Volkswart and at times the Kommunistische Arbeiterzung were the available, representative newspapers.9

In practical terms all these efforts came to nothing. Seeckt made it clear that he would put down any ‘national-communist uprising’. In the meantime, National Socialist groups formed; the KPD proscribed the Hamburg circles; and the connective threads in Hamburg between men like Stapel, A.E. Günther††, and a number of nationalist youth leaders that had led to the National Communists were torn away again. Wolffheim, who in Hamburg had power in his hands on November 6th, 1918, was neutralized by the ‘revolution’ of the National Assembly.‡‡

Later, the Ruhrkampf§§ once again led to the revival of these tendencies.

After Schlageter’s execution in 1923, Karl Radek on the 20th of June delivered to the Central Committee of the KPD his famous speech titled “Schlageter, the Wanderer into the Void”10, which called on the honest nationalists to integrate into the front of red revolution which alone would fight for national freedom, as the Ruhrkampf was being betrayed yet again by the bourgeoisie. The debate between the communists Radek & Fröhlich and the nationalists Reventlow & Moeller van den Bruck over “going a bit of the way together” was thereupon initiated in the ‘Roten Fahne’, the völkisch ‘Reichswart’ of Count Reventlow, and the ‘Ring’ of Baron von Gleichen; likewise that too eventually failed.***

Radek’s line was abandoned first by the KPD. Wolffheim remained, for the most part, alone.

In 1929(11) these concepts, which had in the meantime become worked out ever more clearly and concretely, were revived again by the other side – this time by the right.

First in the Jungen Volk, then in the Kommenden – two newspapers of the nationalrevolutionary youth – were National Bolshevist demands discussed. In a special edition which committed itself to the class struggle, to the complete socialization of resources, and to a Greater German council-state, the National Bolsheviks for the first time presented themselves to the general public; Ascension Day 1930 thus saw the ‘Group of Social-Revolutionary Nationalists’ establish themselves around the National Bolshevist theses and the foundational work, “Social-Revolutionary Nationalism” [“Sozialrevolutionärer Nationalismus”]. 12 From here the other nationalrevolutionary groups became more and more infected with this tendency. The Socialist Nation became the national-communist mouthpiece.

Such a ‘National Bolshevist’ position is today no longer so surprising as it was years ago. Ever more circles of people, especially of the younger generation, are today of anti-capitalist disposition, are through their mindset ‘National Bolsheviks’ even if they do not use the term. And where does one still find youth today who, turning their attentive eyes on their era, on the unemployment offices and working-districts, are still willing to justify and defend a social order that prevents 95% of the German people having any share at all in what they’re supposed to call their Fatherland?

It is the honest prerogative of youth to break down the old defences, and youth defines the features of German National Bolshevism.

Daily do we realize how right Frank Thiess††† was (one of the few of our fathers’ generation who joined with us), when he observed:

“In Germany today a new faith is emerging. A faith in the autonomy and hyper-reality of the nation. In the inescapability of their unifying compulsion. In the immutability of our destiny. In the indestructible force of our will to live.

“Only at a time of the greatest economic hardship and unspeakable adversity could there be raised, over this life of destitution and austerity, a dome of faith in the unified lives of the nation. Only at a time of national misfortune is a genuine national worldview possible. Indeed, the will to a new order of divergent parts pushes us towards a new state ethos, but such ideals do not spring into the world overnight, rather they fulfil themselves in spasms of crises over the course of decades. There are long years of disappointment, hardship, and experience necessary to achieve them.

“A new world begins, a new nation is formed, yes, an invisible revolution is perpetually in progress. Only its outer course has a revolutionary character – the way old truths, whose binding value still had validity a decade ago, are abruptly washed away, and instead there newly emerge objectives which were scarcely taken seriously before (autarchy, nationalism, a classless peoples’-state, bound agriculture, etc.), this swirling speed of events taking place amidst a phenomena that stands there steady like a ‘rocher de bronze’ ‡‡‡ – all this has something of the soundless drumbeats of revolution, an appearance that is magnificent, sinister, and historically unprecedented.”

4 Published in full in vol. 1, no. 3/4 of Socialist Nation.

5 The quote from the English Prime Minister Lloyd George in Vienna’s Neuen Freien Press shows how dangerous this possibility appeared to the status of Versailles: “The steady expansion of communism in Germany represents a grave danger for the whole of Europe. The War has shown what a powerful people the Germans are when they are put to the test. That’s why a Communist Germany would be far more dangerous to the world than Communist Russia… I cannot imagine any greater danger for Europe, yes, for the whole world, than for there to be a great Communist state in Central Europe, directed and maintained by one of the world’s most intelligent and disciplined peoples.”

6 The Treaty of Rapallo, the work of Brockdorff-Rantzau’s friend von Maltzan, was a later consequence of this– but Brockdorff-Rantzau died with the bitter words on his lips, “Everything for me has been shattered – I already died in Versailles.”

7 The Munich communist newspaper Neue Zeitung issued the rallying-cry for armed popular uprising against the Entente.

8 Material about this published in the Wolffheim-Laufenberg Hamburg newspaper Volkswart, no. 6, October 1921. A report: “In the early morning hours of Tuesday, March 16th, a detachment of soldiers from the EhrhardtBrigade arrives at the Reich Chancellery seeking to be received by Kapp. When they are not admitted, they express their discontent in heated words: they have no more desire to continue their involvement in the swindle, since the seizure of the assets of profiteers has not occurred; they have not tagged along to set in place of Ebert a new Wilhelmine government; from Kapp they’ve had a gutful. When it becomes known among the troops that the detachment has not been admitted, they are seized with a tremendous uproar. The last troops which still hold loyal to Kapp erupt in white-hot mutiny. Immediately the shop-stewards of all contingents are mustered together. The assembly takes place towards midday in a hall of the Reich Chancellery, while in an opposite hall the helpless mummies of the old regime are pensively racking their empty brains. In the soldiers’ assembly, the indignation of the shop-stewards, who feel blatantly abused, is vented with unrestrained force. Added to that is the impression that they are situated in the midst of a mousetrap, from which the ring-leaders of the Putsch would certainly know of no way out. All who speak give speeches against the Wilhelmine officers and against the old regime. Under stormy applause, the Ehrhardt-people now call out to one of the national-socialist leaders in the hall: ‘We helped the Reaction get back on its feet again, we must make it clear to the workers that we are not against them, but want to fight with them.’ It is agreed to present their demands to General Lüttwitz. At this moment about 15 young officers rush into the hall, slung with hand-grenades from head to toe. One of them springs atop a table and calls out: ‘Comrades, who is in favour of the military taking charge? Who is in favour of fumigating the hall next door? Who is in favour of doing it the way we thought it was going to be done?’ And to all three questions there follows a unanimous, stormy applause. With rifles inversed, the formations that had just risen against the Kapp regime now move out of the city, where they come across armed workers in Friedenau to whom they shout: ‘We’ve broken with Kapp! We’re leaving!’ But already shots are being fired from the rows of armed workers. The soldiers also tear their guns around and return fire. The carnage begins.”

9 Excerpts from Laufenberg’s writings are reproduced in Socialist Nation, Vol. II, no. 3/4.

10 Published verbatim in Socialist Nation no. 5, vol. I.

11 Reventlow summarized his position in his work Völkisch-Communist Unification? [“VölkischKommunistische Einigung?”], Moeller van den Bruck his in his The Right of Young Peoples [“Recht der jungen Volker”], the KPD theirs in the brochure “Schlageter”.

12 Available from the publisher of the Socialist Nation.

Translator’s Notes

* “Young-Deutschland” in the original text – a reference to the Young Plan, introduced in 1929 as an attempt to spell out more manageable terms for Germany’s Versailles reparations payments, and vigorously opposed by nationalists and by the Communist Party of Germany (KPD).

† Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau was a German diplomat of Prussian noble heritage. Despite his background, he accepted the post of Foreign Minister in the Ebert government after the November 1918 revolution. On June 20, 1919, he resigned his position in protest against the government’s signing of the Treaty of Versailles, deeming it a “crime against Germany.” An advocate of German-Russian rapprochement, he afterwards became ambassador to Soviet Russia until his death in 1928. Although not a National Bolshevik himself, Brockdorff-Rantzau’s writings nonetheless contained both German-nationalist and anti-capitalist sentiments, endearing him to later national-revolutionary radicals.

‡ “Wolffheim-Laufenberg” refers to Fritz Wolffheim and Heinrich Laufenberg, two prominent early National Bolsheviks. Expelled from the nascent KPD in late 1919 for alleged syndicalist tendencies, both subsequently joined the Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD), which practised a more independent line from Moscow. Leaders of the KAPD Hamburg branch, Wolffheim and Laufenberg were staunchly opposed to the Treaty of Versailles and began advocating for a position which would see communists ally tactically with nationalists and the middle-classes against it; this position was dubbed ‘National Bolshevism’, and later criticized directly by Lenin in his pamphlet “Left-Wing Communism”: An Infantile Disorder. Both men were eventually expelled from the KAPD. Wolffheim stayed politically active, drifted in a more völkisch direction, and ended up associated with Paetel’s Group of Social-Revolutionary Nationalists. Laufenberg withdrew from active politics, although he continued to publish articles; he died impoverished in 1932. Wolffheim, who was Jewish, was arrested in 1936 and perished in Ravensbruck Concentration Camp in 1942.

§ The “communist Thomas” is Otto Thomas, editor-in-chief during the early ’20s of the KPD’s Bavarian newspaper Neue Zeitung. Thomas had National Bolshevist leanings, publishing nationalistically-inclined articles in his paper and developing links with the Freikorps Oberland and its leader Josef ‘Beppo’ Römer. These links led to accusations by fellow-communist Otto Graf that Thomas had received clandestine funding for the Neue Zeitung from Munich’s nationalist Chief of Police, Ernst Pöhner. Despite these charges, Thomas remained a KPD member until his death in 1930, continuing to maintain his call for nationalist-communist cooperation. Pöhner himself was, as Paetel indicates, the Chief of Police of Bavaria from 1919 to 1922, in which position he did much to make Bavaria a safe-haven for nationalist radical/terrorist groups. A participant in the Beer Hall Putsch, Pöhner had by his death in 1925 become a member of the bourgeois-nationalist German National Peoples’ Party (Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP).

** Judicial Councillor Fritz Krüpfgantz was a member of the ‘Free Association for the Study of German Communism’, a small, early National Bolshevist intellectual movement founded by Wolffheim and Albert Erich Günther after the former’s expulsion from the KAPD. Krüpfgantz’s “Open Letter” was published in the Free Association’s publications in August 1920 and called on Major-General Lettow-Vorbeck (who had been involved in both the Kapp Putsch and in putting down the Spartakist uprising) to join a ‘German Communism’ (i.e. National Communism) which would bring about national liberation from Germany’s post-War “humiliation”.

†† Wilhelm Stapel and Albrecht Erich Günther were co-editors of the conservative-revolutionary journal Deutsches Volkstum. The Volkstum, formerly the Bühne und Welt, had been bought by the DHV (a nationalist, white-collar workers’ union) in 1918, with Stapel and Günther becoming its leading lights. The Volkstum and its editors rejected the traditional nationalism of the Wilhelmine era, advocated against capitalism, and offered some support and sympathy towards workers’ issues. Despite their anti-capitalist tendencies and their brief alignment with the Hamburg National Bolsheviks in the early ‘20s, both Stapel and Günther later moved towards a more ‘conservative’ position and expressed a wariness about Marxist economic ideals. For the Volkstum, socialism meant not collective ownership, wealth redistribution, or the abolition of private property, but “an ethical restraint on the economy based on professional honour and respect for man.” (For source of quote, see: Roger Woods’s The Conservative Revolution in the Weimar Republic)

‡‡ A reference to the revolutionary workers’ council which ruled Hamburg in the period after the November 1918 revolution, in which both Laufenberg and Wolffheim played prominent roles. The councils ceased to have any legitimate political power after the transition to the new National Assembly was effected with the national elections of 19 January, 1919.

§§ “Ruhrkampf” is the German name for the period of German resistance in the Ruhr. In 1923 the Entente powers France and Belgium sent troops into the Ruhr valley, occupying the area as punishment for Germany’s failure to sufficiently fulfil its obligations under the Treaty of Versailles. A united campaign of resistance resulted, with Germans of all political persuasions banding together to fight back (both through passive and active methods) against the occupying forces.

*** Paetel here is referencing the time of the ‘Schlageter line’, where the execution in 1923 of National Socialist terrorist Albert Leo Schlageter by Franco-Belgian occupation forces in the Ruhr led to a brief period of open collaboration between nationalists and communists. Karl Radek and Paul Fröhlich were prominent communists; the Rote Fahne (‘Red Flag’) was the KPD’s national newspaper. Count Ernst zu Reventlow (publisher of the journal Reichswart), Arthur Moeller van den Bruck (a major contributor to the journal Gewissen, in English “Conscience”), and Baron Heinrich von Gleichen (publisher of the Gewissen, renamed “Ring” in 1927) were prominent nationalists. All these men exchanged articles in one another’s journals during this period, openly discussing and debating völkisch-Marxist collaboration.

††† Frank Thiess (alternately, Frank Thieß) was a German novelist and playwright, originally from the Baltic, who had some conservative-revolutionary leanings. After WWII he was well-known for having coined the term ‘Inner Emigration’ to describe those opposed to National Socialism who, unable to immigrate physically, instead immigrated ‘mentally’ – whether by withdrawing from public life, engaging in resistance work, or by subtly keeping clear of any action that would provide support or legitimacy to the NS regime.

‡‡‡ French for ‘rock of bronze’, an expression used in German and originating from Friedrich Wilhelm I of Prussia. It has a meaning suggesting solidity, lasting strength, unshakeable firmness and power. Friedrich Wilhelm I used the term to describe the authority and sovereignty of the Prussian crown.

Young Nationalism

The youth in Germany are today faced with a concrete decision: Either jeunesse dorée, to be the last contingent of yesterday’s age, in clear acknowledgement of the hopeless situation of the bourgeoisie who have failed politically in every circumstance (the shameless capitulation of the capitalists in the Ruhrkampf before General Dégoutte at the moment state subsidies were cut off is but one of many examples); or else, as socialists, to be the guardians of the original values of German history and even of bourgeois culture, standing in solidarity with the proletariat in their class-struggle without sentimental ‘Proletkult’. There is no compromise solution.

This decision does not cut off German youth from the history of their people. And the facts, around which every political decision must be oriented today, make the choice clear enough:

The lost war, doomed due to its entire structure justifying un-völkisch politics (three-class franchise* ), due to the bourgeoisie’s corruption amidst the commercial tumult – this made us into the most profoundly anti-bourgeois.

The lost revolution, doomed due to the half-measures and lack of instinct on the part of its leaders, lost out of blindness towards the national task of radical upheaval – this made us all the more revolutionary.

The lost sovereignty of Germany, its doom guaranteed by the liberal-capitalist Weimar Republic and sustained through its subordination to Paris and Wall Street – this made us unequivocal nationalists.

The lie of the Volksgemeinschaft† , a lie which defamed the process of renewing the body of the Volk [Volkskörper] and was embodied in the new state’s people-destroying [Volkszerstörend] striving for power – this made of us fighting-comrades in the class-struggle.

The hopeless fate of all post-war generations, the recognition that this fate is contingent on an anti-grass-roots, propertied-bourgeois, capitalist order – this made us into anti-capitalists, made us into socialists.

Unquestionably, the Bündische‡ willingness – as demonstrated by the Jugendbünde, the Freikorps, and so on – to subordinate oneself and one’s own freedom to the ‘We’, to the self-selected ‘collective’, is not to be underestimated. It is pre-political rather than a fact of politics; ultimately it is a pedagogical category.

The Bündische ideal is not a political principle, it does not have to commit itself to a concrete manifestation in German politics. All the theories that the ‘Bündische Front’ can achieve state power tomorrow and will be able to transfer the laws of collective life from young people to the state order are indeed beautiful, but are regardless just romantic utopianism.

The true fronts work differently.

The Youth Movement has many accomplishments. Its educational aspects are undeniable today and can no longer be undone. Politically, however, it has failed all along the line.

In order to evaluate German politics correctly, the Youth Movement has to learn one thing: the significance of the Germany of big cities, the unemployment office, mass actions.

“The Youth Movement is dead! – Long live politics!”

This slogan, which years before closed out a leadership conference of one of the largest Bünde (although there were never any real consequences resulting from it), must be taken seriously at last by every single “Bündische” type.

Then, and only then, will power and success for the whole be pried from the substantial force which undoubtedly exists there.

Being young is not a virtue. And generational conflict is nothing new in the process of biological law. Only when, at the cross-roads of centuries, youth stands at the precipice of a decaying spiritual epochs, does the generational question take on a historical and therefore also political meaning. Even the Youth Movement – not engendered by any aspirations, but born out of the alienation of the lives of the young from the sociological and ideological values of their fathers, taking shape as the struggle for the autonomy of youthful community-life – has no political mission per se. To want to spur on the politics of the Youth Movement as the political fronts of Germany today – a dream that many of us once clung to – is absurd.

Attitude and intellectual openness are not yet political values, birth certificates are not political identity cards. Existential consciousness is only a pre-political basis, never a political criterion.

There are no political duties for the young generation as a whole. (Beyond that, one would have to take into account how much the individual age-groups between 18 and 40 differ today in their basic rhythms.)

But there is an approach for the youth that sees the nation as the central value of their personal lives and their societal function.13

The revolutionary bourgeois youth, which to this day undoubtedly for the most part sees in National Socialism the fulfilment of its vision of combining the national and revolutionary-economic impulses, is the sociological bearer of what the bourgeois call National Bolshevism.

There are no politics for the Jugendbünden, cut off from the fronts of their fathers.

There are no politics for the young generation in the battle of youth against age.14

But there is a mission for young nationalism, particularly the post-War youth, which – after over ten years of the Front-generation’s struggling in vain – only they are able to resolve: to plant the flags of the nation in the camp of the class-struggle, to pass on by the word of mouth the watchword “Germany” in the Heerbann§ of the revolution, to form alongside the formations of the proletarian parties an order of nationalist, anti-bourgeois, and anti-capitalist revolutionaries.

To establish the focal point of immortal Germanness in the camp of today’s Fatherland-less, in readiness of the morrow’s duties: that is the task of

Young Revolutionary Nationalism.

Only there can the questions which face Germany’s youth today be answered.

We do not consider following Oswald Spengler’s counsel: “Endure the lost position of a sinking world,15 like that Roman soldier whose bones were found in front of a gate in Pompeii, who died at his post because, during the eruption of Vesuvius, they had forgotten to relieve him.”16

13 Compare Klaus Mehnert: “The Youth in Soviet Russia” [“Die Jugend in Sowjetrußland”], Fischer Verlag, Berlin.

14 Compare Karl O. Paetel: “The Structure of National Youth” and “The Spiritual Face of National Youth” [“Die Struktur der nationalen Jugend”, “Das geistige Gesicht der nationalen Jugend”], available through the publisher of the Socialist Nation.

15 As an example of how much the representatives of this world feel they are declining, an excerpt from the Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, ed. 139, 23/03/32: “At yesterday’s general assembly of the AEG**, Privy Councillor Dr. Bücher made a statement that shed bright light on the tragedy of the German economy in these months of the most severe crisis. Privy Councillor Bücher said that the ambition of today’s entrepreneur can only be that he is one of the last to find himself interned in the cemetery where the private-capitalist economy is buried, without anyone being able to substitute another sustainable economic system in its place.”

16 Oswald Spengler, “Man and Technics” [“Der Mensch und die Technik”], C. Beck, Munich

Translator’s Notes

* The Prussian ‘three-class franchise’ system was the German electoral system from 1848-1918, which was deliberately structured so as to provide the wealthy greater influence in elections than their proportion of the population would otherwise have warranted.

† The concept of the ‘Volksgemeinschaft’, or classless ‘people’s community’, today tends to be specifically associated with National Socialism as a result of it being a central aspect of NS propaganda. The concept pre-dates the NSDAP, however, and had a measure of popularity among many different groups of differing political persuasions, including segments of the Social-Democrats. The idea of a Germany free of the tensions created by class and status was an attractive one to many, and had been held up as an ideal both by the imperial government during the Great War and by the new Social-Democratic regime after the November Revolution. Paetel’s use of the phrase “the lie of the Volksgemeinshaft” is, based on later comments within the Manifesto, unlikely to be a rejection of the concept itself as inherently dishonest; more likely he is criticizing the (in his eyes) dishonest way the term had been used by the various groups who championed it as a political concept. See in particular the later chapter “The Class Struggle as a Nationalist Demand”.

‡ “Wolffheim-Laufenberg” refers to Fritz Wolffheim and Heinrich Laufenberg, two prominent early National Bolsheviks. Expelled from the nascent KPD in late 1919 for alleged syndicalist tendencies, both subsequently joined the Communist Workers Party of Germany (KAPD), which practised a more independent line from Moscow. Leaders of the KAPD Hamburg branch, Wolffheim and Laufenberg were staunchly opposed to the Treaty of Versailles and began advocating for a position which would see communists ally tactically with nationalists and the middle-classes against it; this position was dubbed ‘National Bolshevism’, and later criticized directly by Lenin in his pamphlet “Left-Wing Communism”: An Infantile Disorder. Both men were eventually expelled from the KAPD. Wolffheim stayed politically active, drifted in a more völkisch direction, and ended up associated with Paetel’s Group of Social-Revolutionary Nationalists. Laufenberg withdrew from active politics, although he continued to publish articles; he died impoverished in 1932. Wolffheim, who was Jewish, was arrested in 1936 and perished in Ravensbruck Concentration Camp in 1942.

§ Much of this chapter deals with the Youth Movement [Jugendbewegung], which played a significant role in German political and cultural life in the pre-WWII era and strongly impacted the development of political and religious youth organizations like the Hitler Youth, the Young Communist League, etc. Originating as a kind of ‘back-to-nature’ movement (the Wandervogel), the German Youth Movement had a strong emphasis on scouting, hiking, camping, and other outdoorsy pursuits. This romantic attachment to the German countryside often led to a reinforcement of nationalist and/or völkisch tendencies in the youth. In the aftermath of the effects of the First World War, this ingrained national sentiment resulted in a transformation in the Youth Movement – in particular leading to the proliferation of many organized, hierarchical youth organizations, often with a central leadership, their own flags, uniforms and rituals, and a core set of values or beliefs guiding their activities (frequently these ideals were political and nationalist, although not always). These were known as the Bündische Youth (Bündische Jugend, or the Jugendbünde). Bund (plural Bünde) translates as ‘league’, although its meaning in German can be a little more evocative, suggestive of a more organic, communal association between members than that of related terms like Orden (‘order’). Many of the Bünde came to see the Bündische ideal – which they experienced as a kind of communal, meritocratic brotherhood guided by charismatic leadership – as offering a prototype for a future organic German community or state. Paetel himself had been a leader in the Deutsche Freischarr, one of the largest Bündische scouting organizations; his experience with the Bünde and with the Bündische ideological concept is what motivates his critiques and criticisms in this chapter.

** “AEG” = ‘Allgemeine Elektricitäts-Gesellschaft’, or ‘General Electricity Company’. A major electronics producer and power company.

Reformed National Socialism?

Some time ago there came from the press an announcement of the founding of a ‘German-Socialist Party’ * which had set itself the goal of uniting the miscellaneous National Socialist splinter-groups and secessionists and, as a kind of purified National Socialism, to honor the promises not fulfilled by Adolf Hitler and to re-occupy the political position he had abandoned – anticipating that the true National Socialists, after recognizing the betrayal of their previous leaders, would turn instead to the reformers.

The claim to represent ‘true National Socialism’ is not new. Both the Fighting Community of Revolutionary National Socialists – which constitutes the core of the ‘Black Front’ led by Dr. Otto Strasser (actually, both the shell and the core are identical!† ) – as well as the Independent National Socialist Combat Movement of Germany of Captain Stennes, make such a claim.

The numerical weakness of these groups is not an argument against their political capabilities. The evolution of the Hitler-party has made one sufficiently sceptical of the superiority of the ‘Big Boys’ against the ‘splinters’.

But following from the political and societal function of such front-formations, what remains is the basic inquiry into, and following that the search for, the historical departure point for a ‘reformed National Socialism’.

The main reason why every attempt at reform (an approach which puts their mission in the wrong from the very beginning) involves turning against the NSDAP is due to the accusation of personal inadequacy against the old Party leaders, of the leaders’ deviation from the old (and in principle correct) 25-point line, as well as their pursuit of the wrong tactical measures.

They all want to be National Socialists, those who turn against the unsatisfactory Hitler, against the influence of the big shots‡ [Bonzokratie], against the creeping bourgeois mentality, against the Brown House, against the incorrect ‘legal’ measures of the Party leadership, each believing themselves to be the one in possession of the true ring§ . Otto Strasser has to that end provided the framework of a ‘Worldview of the 20th Century’; Captain Stennes appeals to the revolutionary sentiment and yearning of the SA-members; the German-Socialist Party is turning away from the incorrect measures of the last quarter.**

And here is the breaking-point of all these attempts. Being an opposition group can be valuable. The fate of the various oppositions within the Marxist camp, however, shows clearly enough that the most auspicious fate awaiting an opposition is that its arguments (three quarters of which are only ever in respect to tactical differences) will one day be silently accepted, with the ‘conscience of the party’ thereupon, without any further ado, shedding its entire reason for existence.

If, however, the real failure of the Hitler-party is not due to the inadequacy of its leading personalities, but is based instead in the party’s fundamentally poor decisions, then any such reformer misses the core issue and becomes a miniature copy of the bigger brother, never the bearer of historical laws.

Translator’s Notes

* The term ‘German Socialism’ was often used interchangeably with ‘National Socialism’ – both were intended to denote a socialism that was the antithesis of the internationalist, ‘un-German’ ideology of Marx and Engels. One of the earliest National Socialist parties in Germany was called the ‘German Socialist Party’ – founded in 1918 (a few months before Anton Drexler’s German Workers’ Party), it was for a brief period the largest and most prominent NS party in the country, fêted by National Socialists in Austria and the Sudetenland, before its eventual absorption into the NSDAP in 1922. The party Paetel is actually referring to here was a fairly minor group which had split off from the NSDAP sometime around August 1932: the German Socialist Workers’ Party (Deutsche Sozialistische Arbeiterpartei, DSAP), occasionally also referred to as the ‘German Socialist Party’ or ‘German Social Party’. Its leaders, Arno Franke and Wilhelm Klute, had both been active NSDAP members (although Franke had started off his political career as a Social-Democrat) and both had become bitterly disappointed with the Party over time, particularly with its organizational structure and with what they perceived as the poor qualities of its local leadership. The DSAP was intended to advance a more pronounced socialist line while avoiding the corruption and authoritarianism which Klute and Franke alleged was dragging down the NSDAP; its leaders thus hoped that it would draw in all those of National Socialist disposition who were nonetheless wary of Hitler or other prominent Party figures. The group at its peak never had more than 2000 members, and its activity was concentrated solely within Berlin and parts of Saxony. Like the other National Socialist splinter-groups (of which there were many in the early ‘30s), the DSAP was banned after Hitler assumed power. Klute survived past the end of the War, but Franke was arrested in 1933 and likely died in a concentration camp.

† In German, ‘Bonzen’ means ‘bosses’ or ‘bigwigs’. ‘Bonzokratie’ thus means something like ‘rule by big shots’ or ‘influence of the bosses’, or more simply ‘bossdom’. It is also occasionally translated as ‘oligarchy’; this in my opinion is inaccurate, as it removes some of the deeper significance behind the word, which had particular meaning for National Socialists. Criticisms from within the Party against the leadership (typically made by members of the SA against Party functionaries) would often involve throwing around the term Bonzen, implying that the leaders were out-of-touch, snobbish, and high-handed, no better than the capitalists who National Socialism claimed to be fighting against.

‡ Likely a reference to the ‘Ring Parable’ of Gotthold Lessing’s play Nathan the Wise. In the play, the character Nathan relates a story to Saladin about a father who left his sons three rings, only one of which was magical; the others were physically identical but mundane copies. The three brothers quarrelled over ownership of the ‘real’ ring, until finally set straight by a wiser man. The story is intended as a parable about religious faith, but Paetel here is using it as an analogy for the squabbling of National Socialist splinter-groups over who is the bearer of the ‘real’ National Socialist doctrine.

§ The mention of Otto Strasser here is a reference to his 1929 book National Socialism – Worldview of the 20th Century [“Der Nationalsozialismus – die Weltanschauung des 20. Jahrhunderts”]. Captain Walter Stennes was a former leader of the Berlin SA who in March 1931 led a Brownshirt rebellion (the ‘Stennes-Putsch’) against the NSDAP leadership, before leaving to form his own group, which after some factional troubles of its own eventually took the name ‘Independent National Socialist Combat Movement of Germany’ [“Unabhängige Nationalsozialistische Kampfbewegung Deutschlands”].

———————————————————————————

The Fascist Mistake

The disastrously misjudged historical mission of that which quite justifiably might have been called ‘national-socialism’ * can already be seen in the Hitler-party’s first months of work in 1919, in which the anti-statist resentments against Berlin (which are practically a philosophy of life on the other side of the ‘Main line’ † , where it is preferred to look to Rome rather than to the land of the ‘Prussian Gau’) were underlined by a pronounced historical mistake, a mistake which definitively rejected the character of the ‘Germanic uprising’ against Paris.

At the moment when those under Versailles alone were capable of making history, the slogan of rebellion against Versailles was supplemented by the domestic-political slogan “Against Marxism”, turning on its head the willingness to, in the Party’s name, take the side of the destitute or homeless, the Fatherland-less, in order to create for them a homeland17 via radical change to societal and economic life. Upon realizing that the demand of the hour was “Through Socialism to the Nation”, the calculation of the fascist propertied-bourgeoisie became: “Beat Marxism – and you eliminate Volk-destructive class-stratification!’

Thus the principle that the NSDAP committed itself to was false from the start, which therefore dooms to failure every attempted renaissance of its spirit which reaffirms that same principle.

A look at the development of Italian fascism demonstrates the inevitable, obligatory lawfulness of such a fighting position. In recent months Dr. K.A. Wittfogel‡ was unequivocally able to prove, on the basis of old ideological texts18, that the first fascist programmes bore a thoroughly revolutionary socialist character, roughly equivalent to the German USPD. So long as the Fascios stood by these demands, they simply remained one among many troublemaking frontline fighters’ associations. At the moment, however – just as occurred in Germany in 1919 – in which the bourgeoisie, menaced by the “Bolshevik wave”, recognized the chance to deploy these militant forces for its own security, then fascism emerged theoretically and practically as an anti-Marxist force and unambiguously assumed a societal function as a security organization for the establishment.

When on the first of May the cells of fascist railwaymen made it impossible to carry out a general strike for the first time in Italy; when the fascist fighting-leagues, with clandestine support from the government, liquidated the syndicalist occupation of the factories; then had Mussolini, completely ignoring the old radical points of his programme, created the psychological conditions for the anti-Bolshevik forces to more or less gladly clear the way for the establishment of ‘Peace and Order’.

17 Moeller van den Bruck put it perfectly in The Third Reich [“Das dritte Reich”] (Hanseatic Publishing House, Hamburg): “It is intolerable that the nation should have permanently under its feet a proletariat that shares its speech, its history and its fate, without forming an integral part of it… The younger proletarians are already beginning to prick up their ears when they hear talk of a country of their fathers which the sons must conquer if it is to become the possession of their children.” Bebel too formulated it well at the 1907 ‘International Socialist Congress in Stuttgart’: “What we are fighting is not the Fatherland itself, which belongs to the proletariat far more than to the ruling classes, but the conditions which prevail in the Fatherland in the interests of the ruling classes.” And even Bismarck recognized this very well. In all his political speeches we see again and again the need to defend himself against the reproach of “State Socialism.”

18 Der Rote Aufbau, 1932, Nr. 16.

Translator’s Notes

* ‘national-socialism’ – In German the term ‘National Socialism’, i.e. the ideology of National Socialism as championed by the NSDAP, is written as a single word: ‘Nationalsozialismus’. Paetel in the German very deliberately uses in this sentence a two-word alternative instead, ‘Nationaler Sozialismus’. Both have the exact same translation in English, but the different ways they are written conveys a different sense of meaning – Paetel here is drawing a clear distinction between the concept of a ‘national-socialism’ (which he obviously approves of) and the formal ideology of National Socialism as propagated by the NSDAP. To make Paetel’s distinction clearer, I have written the term in a slightly different style.

† The ‘Main line’ (‘Mainlinie’) is the line between North and South Germany, which historically demarcated the political spheres of influence of Austria and Prussia within the old German Confederation. By the time of Paetel’s writing the term was used to refer to the division of political, cultural, religious, etc. differences between the North of the country (dominated by Prussia) and the South (dominated by Bavaria). Paetel’s remark that those in the South “preferred to look to Rome” is a reference to Bavaria’s Catholicism, a religion seen by some radical nationalists as a foreign imposition (sometimes referred to as “the Black International”, as opposed to the “Red International” of Marxism and the “Gold International” of capitalism) with an alleged pernicious, centralizing, authoritarian political and cultural impact.

‡ Karl August Wittfogel was a playwright, sociologist and Sinologist, and one of the Communist Party of Germany’s more prominent intellectual figures. He was a frequent contributor on cultural issues to a number of Marxist journals, and was the author of several successful, socialist-themed expressionist plays. Wittfogel was considered an expert on China, a nation he spent much time in as a researcher; his experiences in China in part influenced his eventual break with communism around 1939-40. By the Cold War period he had become stridently anti-communist.

The Historical Error of the NSDAP

The parallel is obvious. The seven-man-council in Munich, as an anti-Versailles force and likewise through its ‘alignment’ (the emotional anticapitalism of “breaking the bondage of interest”, only attractive to the uprooted, revolutionary layers of radicalized front-soldiers, students, etc.), became a piece on the chessboard of sluggishly reviving bourgeois politics at the moment it became clear that from them (with the bourgeoisie’s gracious toleration of their youthful exuberance in expressing radical feelings) the forces could be formed that would be able to push back against the advancing Marxist working-class and, possibly, be in the position to eliminate them.

In a situation where the urgent decision to be made on the class forces was increasingly clear-cut, whoever took up the slogan “Against Marxism” in the battle between Capital and Labor had to remain willingly or unwillingly indifferent out of necessity, in order to be able to side with those who had every interest in repudiating Marxism’s political and economic claims to power.

Finance-capital and large landowners, jobless officers and restoration-obsessed feudal lords, all could at that moment overlook a few programmatic blemishes, since they still demonstrated the NSDAP’s possibilities for returning the distribution of power in German politics back to its old state.

The blame for this development does not lie with the incapable Osaf Herr Stennes, Herr Strasser, or even with Herr Schulze* , who were likewise powerless to escape from the internal dynamic.

One may reject certain points of the Marxist program, one may maintain that its worldview is deficient and out-of-date, but one will refute it neither by coaxing nor with Stormtroopers.19 It can only be overcome from within itself. Russia shows that. As a nationalist, one’s thinking on German politics today must be in terms of forces, not ideologies.20

One the one hand, there is today a government whose domestic policies signify the darkest Reaction; the further intensification of class distinctions; the creation of a living ‘subhumanity’ under the state of exception† in which the national unity necessary for achieving sovereignty is thoroughly weakened; a foreign policy directed towards France, with Christian intentions of intervention; and the fascist movement as the exultant trustee of the bourgeois legacy, united with the propertied middleclasses and incapable of national liberation as well as of socialist revolution. – And, on the other hand, there are the revolutionary working-classes, organized in and with the KPD, negating the fundamental principles of foreign-policy-enslavement from Versailles to Young, and ready for the revolutionary deed which will transfer the economy into the hands of the whole, making the Fatherland-less the stewards of the new Fatherland that will create the nation…21

With such a clear and hopeless separation between the two, revolutionary nationalism cannot wait around as a ‘Third Front’ until both are rendered obsolete and internally overcome – otherwise the ‘Third Front’ will become, as per Hans Zehrer, the ‘Front of Last Authority’, the Reichswehr‡ . Revolutionary nationalism must take sides. In other words, to unambiguously be a fighting-comrade, to be with the anti-Versailles forces, to be with the formations that want to fight for the Socialist Fatherland of tomorrow, one must therefore belong at the side of the KPD where the struggle for work, the nation, and socialism is being fought, where the class-struggle is affirmed as the path to revolution.22

19 “One cannot kill Marxism with a rifle-butt, but must give the Volk a new idea!” (General Ludendorff before the court, 1924)

20 The recognition that today the egotistical age of liberalism is being superseded by socialist communitarianism is undoubtedly correct. But to make a straightjacket out of a ‘law’ calculated in annual figures demonstrates only a complete inability to think historically.

21 Karl Radek, “The Comintern’s Struggle against Versailles and against Capital’s Offensive” [“Der Kampf der Komintern gegen Versailles und gegen die Offensive des Kapitals”], 1922: “This Republic does not have the guts to say: ‘We cease to be a nation, we are a colony of European capital,’ and even less does it have the guts to tell the masses: ‘Today we must submit, but we want to make ready for battle.’ The German working-class will never come to power if it is not able to give the broad masses of the German people the confidence that they will fight with all their might to shake off the yoke of foreign capital.”

22 That will only be possible, however, if one puts aside such ‘witty’ descriptions as A.E. Günther’s: “Marx has constituted the proletariat as a secularized ghetto, thus implanting in it the subversive character that is effective in the class struggle.”

Translator’s Notes

* ‘Osaf’ is shorthand for ‘Oberste Sturmabteilung Führung’ [‘Supreme SA Leadership’], the SA general staff – Paetel here is referencing Stennes’s previous high position of command within the Stormtroopers. “Herr Strasser” is Otto Strasser rather than Gregor, who by this point had resigned all his Party offices and was a backbencher on the verge of complete retirement. The identity of “Herr Schulze” is less clear. Possibly Paetel means Karl Schulz, leader of the German National Socialist Workers Party (DNSAP) in Austria. The DNSAP was older than the NSDAP, and had split in the mid-‘20s over the question of whether or not to submit itself to Hitler’s leadership. The pro-Hitler forces left the DNSAP, which Schulz then headed unopposed. By the time of the Manifesto’s publication the DNSAP had dwindled to a shadow of its former self, unable to compete against the vitality and popularity of the Hitler-movement, but Schulz still maintained some cachet with National Socialists in German-speaking territories as the last remaining representative of pre-Hitlerian National Socialism.

† The ‘state of exception’ is a political concept devised by Carl Schmitt, an influential jurist and political scientist with strong National Socialist and conservative-revolutionary leanings. Schmitt’s writing on the state of exception was intended to provide a theoretical explanation for what was often regarded as a juridical anomaly: the capacity of a supposedly absolute legal system to contain within itself the means of its own suspension (i.e. martial law, a state of emergency, etc.). Paetel’s use of the term here is likely a reference to Article 48 of the Weimar Constitution, which allowed the President to rule by decree and had been a constant in German political life since the time of Brüning’s chancellorship.

‡ Hans Zehrer was a social-nationalist intellectual and the editor of Die Tat [“The Deed”], a widely-read conservativerevolutionary intellectual journal. Zehrer rejected the concept of political parties and had been one of the behind-the-scenes intellectual architects of General Schleicher’s attempts to create a broad coalition (the ‘Querfront’, i.e. ‘cross-front’) between the army, trade unions, and the followers of Gregor Strasser. For Zehrer, enduring institutions like the Reichswehr had far more claim to form the political basis of the state than squabbling, transitory political parties.

Nationalist Communism

From the beginning, a succession of relatively small ‘far-right’ groups have kept their distance from the NSDAP (their spokesmen never having associated with the Party), which today consciously stands against them because they are “national-communist” and anti-fascist.

The more apparent it becomes that Adolf Hitler is unable to honor his promises, the promises with which he today holds the columns of idealistic anticapitalist youth (the young, already thoroughly sociologically-uprooted bourgeoisie) under his banner alongside the crowds of people anxious to safeguard their own interests, the closer the hour comes when in Germany the long-mocked and long-scorned position of National Communism can be realized.

Today we are still ‘Utopians’. But the far-sighted among the ‘conservative’ Grailkeepers already see the danger for them approaching on the horizon. Albrecht Erich Günther23, the co-editor of the Deutsche Volkstum, wrote: “In the nationalrevolutionary youth, which provides momentum to the ‘national opposition’, a deep suspicion sets in: shall we one day be led as ‘white’ storm-columns against a ‘red’ flood? These and other insights awaken mistrust against the foreign policy of credithungry business groups, so it stands to reason to decide against ‘white’ – that is, for ‘red’: National Bolshevism… If we are on the right track in this attempt at interpretation, so can we also predict that, the moment the exponents of economic reason gain influence over the national opposition and bring them not economic relief but instead a new subjugation to France, the National Socialist masses undergo a transformation in their state of being. They become National Bolsheviks. National Bolshevism will then attain the same fervour as that of National Socialism, but it will also be directed against German entrepreneurship, perhaps by a different ecstatic ‘Drummer’.”24 This analysis, written at the time of the Brüning government, is still valid. It particularly applies to Hitler’s situation.*

And the conservative politician who “expects a lot from National Socialism” already knows what it portends for bourgeois-nationalist politics when he beseechingly continues:

“The strength of National Bolshevism cannot be discerned from the membership of a party or group, nor from the circulation of periodicals. One must have a feeling for the youth’s willingness to decide for National Bolshevism in order to grasp how suddenly such a movement can spring from a circle of sectarians into the Volk.”

If the failure of the Hitler-party becomes clearly obvious – following from its renunciation of economic restructuring and socialist construction, and following from its readiness to leave the Treaty Series† untouched25 – then the activist, revolutionary forces who will be freed from it as a result will not be able to be maintained with half-measures, as the ‘oppositions’ offer, but will want to go completely over to the side of socialism.

The largest percentage of the people however will not go over to the KPD, out of the deep suspicion that its national sentiment is mere tactics and not grounded in its innermost being.26

Here then is the mission of German National Communism: to form the cadres who are prepared, for the sake of the nation, to sever all bourgeois ties, who no longer have any relationship with the values and judgements of their fathers since they were plucked from their jobs, studies, and careers and turfed out onto the street – and who, for precisely that reason, want Germany, a Germany that is their own.

The mission of the national-revolutionary groups is to be the rallying-point of those who, in a fighting-community with the Marxist KPD, form a front of those revolutionaries and socialists who as non-materialists avow the nation as the ultimate value, but who are also ready for a radical revolution for the sake of the nation, because only that creates the preconditions for nation-building.

Three different things make this political position politically effective:

Consistent will: To be socialists in the truest sense of the word.

To become aware of oneself as non-Marxists: To be nationalists of faith and knowledge.

And the fundamental rejection of any desire and attempt to reform National Socialism.

Not reformed National Socialism, but a bloc of uncompromising young-nationalist forces in Germany, with steadfast socialist will, unwavering nationalist faith, recognition of the practical situation conferred through Versailles, fightingcomradeship with the KPD.

Only in this way (and not in the fashion being muttered about today by those who, in reality, only mean National Socialism without Hitler, and who want to pull the rug out from under the KPD) is the formation of an organized German National Communism worthwhile. The KPD will become its compatriot, and fascism and quasifascism will find in it their most dangerous opponent. It will have to step forward when the time is right.

23 Günther may like to be reminded of the time he wrote to the National Communist Wolffheim that he: “would have in mind a policy that is in no way contrary to your aims” and “still profess myself to the views that you have expressed.” (September 15th, 1920)

24 From the Deutsches Volkstum, December 1931, “Between White and Red.”